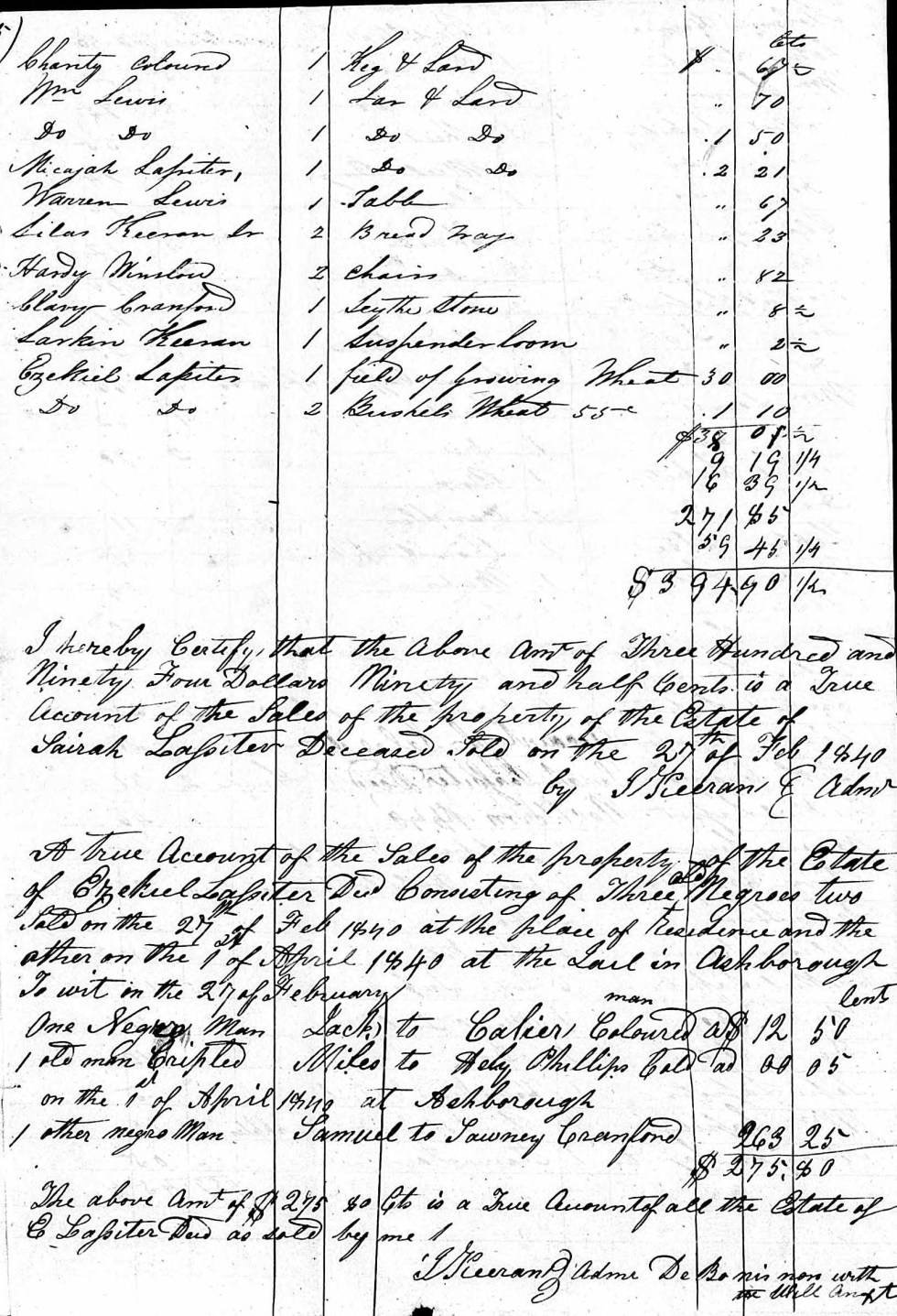

Miles and Healy Phillips Lassiter lived in Randolph County, North Carolina. They were my 4th great grandparents. Miles was born around 1777, and Healy around 1780. Miles was enslaved and Healy was a free woman of color. Thus, all seven children were born free, because a child took its legal status from its mother. The children were: Emsley Phillips Lassiter, Abigail Phillips Lassiter, Colier Phillips Lassiter, Susannah Phillips Lassiter, Wiley Phillips Lassiter, Nancy Phillips Lassiter, and Jane Phillips Lassiter. All the children, except Emsley, lived their entire lives in North Carolina.

The Children of Miles Lassiter and Healy Phillips

Emsley Phillips Lassiter was born about 1811, in Randolph County. About 1832, Emsley emigrated with a Quaker neighbor, Henry Newby, to Indiana.[1] He settled first in Carthage, in Rush County, but eventually moved to an area called “the Beech,” an independent community of mixed-race individuals mostly from northeastern North Carolina and Southside Virginia.[2] There Emsley met and married Elizabeth Winburn, daughter of Tommy Winburn and Anna James, originally from Halifax County, North Carolina.[3] They raised nine children: Sarah, Elizabeth, Nancy, Misa, Wiley, Cristena, William, Mary Anna, and Anna. Emsley died 10 March 1892, in Indianapolis. His wife, Elizabeth, died 21 April 1908, in Marion, Grant County, Indiana.[4]

Abigail Phillips Lassiter was born about September 1812, in Randolph County. She never married. She spent her whole life on the family farm. She died about 1920 (no death record has been found).[5] There is little information about her life. One detail about her life is that she was blind in her last years. Her grandniece, Kate, was often tasked with helping her get around. There is no way to know whether her blindness was due to cataracts, glaucoma, or macular degeneration, all conditions that can afflict the elderly. Abigail is buried in an unmarked grave in Strieby Congregational Church Cemetery.[6]

Colier Phillips Lassiter was born 6 November 1815, in Randolph County, according to family records.[7] With Emsley having moved away, records indicate that Colier fulfilled the roll of eldest son. This was evident after their father Miles died in 1850. Although most of his siblings lived on the family farm, he was the one who handled all the legal and financial transactions.[8] Colier was a respected member of the Lassiter Mill community as evidenced by being a delegate to the Constitutional Congress of the State of North Carolina, after the Civil War.[9] Colier married Katherine Polk, daughter of Mary “Polly” Polk and John McLeod.[10] Together, Colier and Kate had five children, four of which lived to adulthood: Bethana Martitia, Spinks (who died in infancy), Amos Barzilla, Rhodemia Charity, and Ulysses Winston.[11] Colier died about 1887. Because the family says he was a Quaker, it is believed he was buried in the Uwharrie Friends Cemetery.[12] Kate died 19 December 1906 and is buried in Strieby Congregational Church Cemetery.[13]

Susannah Phillips Lassiter was born about 3 October 1817, in Randolph County, according to family documents.[14] Very little is known about her. She is not found in any records after 1850 and is considered to have died before 1860.

Wiley Phillips Lassiter was born about 13 May 1820, in Randolph County, according to family documents.[15] Wiley was a carpenter/cabinetmaker/painter. He had a thriving business, including making carriages for a community store-owner, Michael Bingham. In a lawsuit, Bingham claimed that Wiley owed him money, but Wiley counter-sued stating that Bingham had not paid for several carriages and horses Wiley had on-sale at the store.[16] To pay for his legal expenses Wiley mortgaged his land. The court ruled in Wiley’s favor at first, but when Bingham died, it reversed itself. Wiley lost all his property. He had to borrow money in order to pay his legal debts. He took his wife, Elizabeth Ridge Lassiter[17] and their children to Fayetteville, in order to find more work. He was partially successful, but not enough so. His inability to pay some of his loans resulted in one creditor publishing in the newspapers that he would have to sell Wiley, even though he was born free, in order to recoup his loan to Wiley.[18] The sale did not happen. Based on a letter written later from Wiley to his brother Colier, it appears he was able to get a loan from not only his brother, but also from a family friend. However, there was a new twist. Wiley and his family were very sick, possibly with scarlet fever which had become epidemic about 1858, which made it very difficult for him to work and make the needed monies to repay his loans. Exactly what happened after that is unclear. He was still alive and free in 1860,[19] but apparently died sometime after that and before 1870, when his widow and children were found living in Randolph County again.[20] Wiley and Elizabeth had eight children: Parthenia, Abagail, Nancy Jane, Julia Anna, Martha, John, Addison B., and Thomas Emery.[21] Elizabeth was not found in any records after 1870 and is assumed to have died at that time.

Nancy Phillips Lassiter was born in February 1823, in Randolph County, according to family documents.[22] She was my 3rd great grandmother. She married Calvin Dunson, a blacksmith, about 1856, however, there is no record extant.[23] Nancy had one daughter, Ellen (my 2nd great grandmother), before marrying Calvin. With Calvin she had four children: Sarah Rebecca, Harris, Mary Adelaide, and Martha Ann.[24] The family lived on the family farm. After her death, about 1890, her daughters Ellen and Adelaide began feuding over their shares of the land. The feud resulted in a lawsuit and legal division of the land among all the descendants of Nancy’s father, Miles Lassiter.[25] Nancy is buried in the Old City Cemetery, in Asheboro, Randolph County.[26]

Jane Phillips Lassiter was born 7 January 1825, in Randolph County, according to family documents.[27] There is not much information about her life. It appears she never married. She is not in the 1860 census, but Wiley Lassiter’s 1858 letter to his brother references her assistance to his family who were all sick. They were living in Fayetteville at the time.[28] Jane was apparently living in Salisbury, in Rowan County, in 1870.[29] She was awarded a share of the family farm in the 1893 court decision that divided the family property among all the heirs of her father, Miles Lassiter.[30] There is no reference to her after that.

References

[1] Williams, M. L. (2014). The Emsley Lassiter Family of Randolph County, North Carolina and Rush County, Indiana. Journal of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society, 32:59-78. See also: Williams, M. L. (17 February 2019) Blogpost: #52Ancestors – At the Library – Emsley Phillips Lassiter in the Lawrence Carter Papers. Personal Prologue.

[2] Vincent, S. A. (1999). Southern Seed, Northern Soil: African-American Farm Communities in the Midwest, 1765-1900 (Bloomington & Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press).

[3] Indiana, Marriages, 1810-2001 [Database on-line]. Emsley Lassiter and Elizabeth Winburn married: 28 March 1845, Rush County. Retrieved from: Ancestry.com

[4] Williams, M. L. (2014). The Emsley Lassiter Family of Randolph County, North Carolina and Rush County, Indiana. Journal of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society, 32:59-78.

[5] Williams, M. L. (2011). Some Descendants of Miles Lassiter: Abigail Lassiter. Miles Lassiter (Circa 1777-1850) An Early African American Quaker from Lassiter Mill, Randolph County, North Carolina: My Research Journey to Home (Palm Coast, FL & Crofton, KY: Backintyme Publishing) 105.

[6] Williams, M. L. (2011). Some Descendants of Miles Lassiter: Abigail Lassiter. Miles Lassiter (Circa 1777-1850) An Early African American Quaker from Lassiter Mill, Randolph County, North Carolina: My Research Journey to Home (Palm Coast, FL & Crofton, KY: Backintyme Publishing) 107.

[7] Williams, M. L. (2011). Some Descendants of Miles Lassiter: Colier Lassiter. Miles Lassiter (Circa 1777-1850) An Early African American Quaker from Lassiter Mill, Randolph County, North Carolina: My Research Journey to Home (Palm Coast, FL & Crofton, KY: Backintyme Publishing) 107.

[8] Williams, M. L. (2011). Some Descendants of Miles Lassiter: Colier Lassiter. Miles Lassiter (Circa 1777-1850) An Early African American Quaker from Lassiter Mill, Randolph County, North Carolina: My Research Journey to Home (Palm Coast, FL & Crofton, KY: Backintyme Publishing) 107-110.

[9] Calvin [sic] Lassiter, in Delegates to the Constitutional Congress, North Carolina, Lassiter Mills District. Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, NARA #843-32:107.

[10] North Carolina, Marriage Records, 1741-2011[Database on-line]. Calier Lassiter and Catherine Polk married: 26 September 1854, Randolph County. Retrieved from: Ancestry.com

[11] Williams, M. L. (2011). Some Descendants of Miles Lassiter: Children of Colier Lassiter and Katherine Polk. Miles Lassiter (Circa 1777-1850) An Early African American Quaker from Lassiter Mill, Randolph County, North Carolina: My Research Journey to Home (Palm Coast, FL & Crofton, KY: Backintyme Publishing) 120-123.

[12] Williams, M. L. (2011). Some Descendants of Miles Lassiter: Colier Lassiter. Miles Lassiter (Circa 1777-1850) An Early African American Quaker from Lassiter Mill, Randolph County, North Carolina: My Research Journey to Home (Palm Coast, FL & Crofton, KY: Backintyme Publishing) 107-110.

[13] U.S., Find A Grave Index, 1600s-Current [Database on-line]. Katie Lasiter Memorial at Strieby Congregational Church Cemetery. Find A Grave. Retrieved from: Findagrave.com

[14] Williams, M. L. (2011). Some Descendants of Miles Lassiter: Susannah Lassiter. Miles Lassiter (Circa 1777-1850) An Early African American Quaker from Lassiter Mill, Randolph County, North Carolina: My Research Journey to Home (Palm Coast, FL & Crofton, KY: Backintyme Publishing) 111.

[15] Williams, M. L. (2011). Some Descendants of Miles Lassiter: Wiley Lassiter. Miles Lassiter (Circa 1777-1850) An Early African American Quaker from Lassiter Mill, Randolph County, North Carolina: My Research Journey to Home (Palm Coast, FL & Crofton, KY: Backintyme Publishing) 111.

[16] Randolph County Genealogical Society. (1981). The Willie Lassiter Petition. The Genealogical Journal, V(1): 38-42.

[18] Williams, M. L. (21 March 2018). Blogpost: #52Ancestors – Week #12, Misfortune: Wiley’s story. Personal Prologue.

[19] 1860 US Federal Census; Fayetteville, Cumberland, North Carolina; Wiley Lassiter (Index says “Sprister”). NARA Roll: M653-894; Page: 248; Image: 497; Family History Library Film: 803894. Retrieved from: Ancestry.com

[20] 1870 US Federal Census: Asheboro, Randolph, North Carolina; Elizabeth Lassiter, head. NARA Roll: M593-1156; Page: 287B; Image: 24; Family History Library Film: 552655. Retrieved from: Ancestry.com

[21] Williams, M. L. (2011). Some Descendants of Miles Lassiter: Children of Wiley Lassiter and Elizabeth Ridge. Miles Lassiter (Circa 1777-1850) An Early African American Quaker from Lassiter Mill, Randolph County, North Carolina: My Research Journey to Home (Palm Coast, FL & Crofton, KY: Backintyme Publishing) 123-126.

[22] Williams, M. L. (2011). Some Descendants of Miles Lassiter: Nancy Lassiter. Miles Lassiter (Circa 1777-1850) An Early African American Quaker from Lassiter Mill, Randolph County, North Carolina: My Research Journey to Home (Palm Coast, FL & Crofton, KY: Backintyme Publishing) 116.

[23] Williams, M. L. (2011). Some Descendants of Miles Lassiter: Nancy Lassiter. Miles Lassiter (Circa 1777-1850) An Early African American Quaker from Lassiter Mill, Randolph County, North Carolina: My Research Journey to Home (Palm Coast, FL & Crofton, KY: Backintyme Publishing) 116-117.

[24] Williams, M. L. (2011). Some Descendants of Miles Lassiter: Children of Nancy Lassiter and Calvin Dunson. Miles Lassiter (Circa 1777-1850) An Early African American Quaker from Lassiter Mill, Randolph County, North Carolina: My Research Journey to Home (Palm Coast, FL & Crofton, KY: Backintyme Publishing) 123-127-130.

[25] Anderson Smitherman, et al., v. Solomon Kearns, et Ux. Deed Book 348:156. Family History Library #0470851. See also: North Carolina, Wills and Probate Records, 1665-1998 [Database on-line]. William Dunston, Probate Date: 1892. Retrieved from: Ancestry.com

[26] U.S., Find A Grave Index, 1700s-Current [Database on-line]. Nancy Dunson Memorial at Asheboro City Cemetery. Find A Grave. Retrieved from: Findagrave.com

[27] Williams, M. L. (2011). Some Descendants of Miles Lassiter: Jane Lassiter. Miles Lassiter (Circa 1777-1850) An Early African American Quaker from Lassiter Mill, Randolph County, North Carolina: My Research Journey to Home (Palm Coast, FL & Crofton, KY: Backintyme Publishing) 119.

[28] Williams, M. L. (2011). Some Descendants of Miles Lassiter: Wiley Lassiter. Miles Lassiter (Circa 1777-1850) An Early African American Quaker from Lassiter Mill, Randolph County, North Carolina: My Research Journey to Home (Palm Coast, FL & Crofton, KY: Backintyme Publishing) 114.

[29] 1870 US Federal Census, Salisbury, Rowan, North Carolina; Jane Knox, head; Jane Lassiter, Domestic Servant; NARA Roll: M593-1158; Page: 580A; Family History Library Film: 552657. Retrieved from: Ancestry.com

[30] Anderson Smitherman, et al., v. Solomon Kearns, et Ux. Randolph County, North Carolina Superior Court Orders and Decrees, 2:308-309. Family History Library Microfilm #0475265. See also: North Carolina, Wills and Probate Records, 1665-1998 [Database on-line]. William Dunston, Probate Date: 1892. Retrieved from: Ancestry.com