Not too long ago, a friend and supporter, Marvin T. Jones (Chowan Discovery Group, Inc.), was researching Freedmen’s Education records in an effort to identify the involvement of members of his community of Winton Triangle in Hertford County, North Carolina. He was reviewing receipts for monies received for rent or other supplies that were signed by Winton Triangle residents when he began to notice receipts referencing both Asheboro and “Uharie.” He downloaded copies and forwarded them to me. I noticed that receipts referencing “Uharie,” were signed by “A. O. Hill.” I was not surprised to learn there was a school in Asheboro, but the school in Uharie (as it was spelled on the receipts) I did not know about. That school was of great interest to me.

Uharie

While researching reports of the American Missionary Association (AMA) for my book, From Hill Town to Strieby: Education and the American Missionary Associaion in the Uwharrie “Back Country” of Randolph County, North Carolina (Backintyme Publishing, Inc., 2016), I came across a reference to a school already existing in the Uwharrie area when the Rev. Islay Walden returned to the area after graduation from the New Brunswick Theological Seminary in New Jersey. I knew from my research that the nearby Quaker community had run a school in the area. I thought the reference in the American Missionary was to that school, but that school was further up the road, closer to the old Uwharrie Friends Meeting House. On the other hand, this Freedmen’s school seems to have been in the Uwharrie, possibly in the area called Hill Town. It may have been the basis of a public school referenced in the article.[1]

Hill Town was said to be called such because of the large number of Hill family members that lived there. Most people have believed that it referred to the descendants of Ned Hill and his wife, Priscilla Mahockley Hill. However, there were also white Hills who lived in the area and A. O. Hill was one of them. Was there a connection between A. O. Hill and those people of color who lived in the Hill Town area of the Uwharrie that would have predisposed him to take responsibility for the school?

“A. O. Hill” was Aaron Orlando Hill, born about 1840, son of Aaron Orlando Hill, Sr. and Miriam Thornburg, Aaron Sr.’s second wife. Aaron Sr. can be found on the 1840,[2] 1850,[3] and 1860[4] censuses. He died in 1863. Ned Hill was a free person of color also known to be living in the area. However, he could not be found any further back than 1850. Since the 1840 census only lists heads of families and enumerates others in the household, including any free people of color and slaves, it was very likely that Ned and his family were living in someone else’s household. The most likely places to look were the homes of any Hill families living in the area. They could have been living in some other family’s home, but the logical place to start was with Hill family members. After researching each of the families, it turned out that the only Hill family with free people of color living with them was Aaron Orlando Hill Sr.[5]

The Aaron Hill family were Quakers. It seems reasonable that he would have free people of color living with him. Ned’s family originally may have been slaves of Aaron’s parents, before Quakers condemned slavery and began freeing their slaves as well as helping slaves of non-Quakers to gain their freedom. There were six free people of color living in Aaron’s household. Ned and Priscilla had four known children living at the time of the 1840 census (Nathan, Charity, Calvin, and Emsley),[6] which would equal six individuals. As stated above, Aaron’s was the only Hill household with any free people of color. While currently not proven beyond any doubt, the evidence supports the probability that these six people were Ned and his family. Certainly, such a close relationship and his Quaker background could have predisposed the younger Aaron to be willing to take responsibility for the Freedmen’s school that served the Uwharrie community.

By the time the Rev. Islay Walden had returned to the community in 1880, to begin his missionary work and start a school under the auspices of the American Missionary Association (AMA), Hill Town and the neighboring Lassiter Mill community were already primed to want a school and the educational opportunities it would bring. It was a logical next step to build their own school with the help of the AMA. Thus, Hill Town, which would later become Strieby, apparently already had a strong tradition of education by the time Walden returned, making them eager to have a school over which they could exercise leadership and direction for the first time. The Uwharrie Friends School and the Freedmen’s School had prepared them for this.

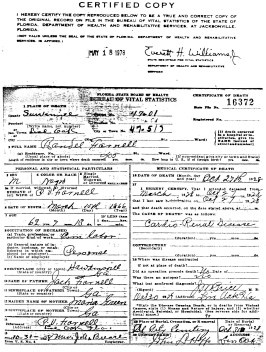

Aaron Hill did not remain in Randolph County. By the time Islay Walden was actively building the church and school in Hill Town, Aaron had moved to Carthage, in Rush County, Indiana, where many other Quakers, including several of his old neighbors from Randolph County, had moved. He died there in 1926.[7]

[1] Roy, J. E. (1879). The Freedmen. The American Missionary, 33(11), 334-335. Retrieved from: Project Gutenberg

[2] 1840 US Federal Census, South Division, Randolph County, North Carolina; Aaron Hill, head. NARA Roll: 369; Page: 77; Image: 160; Family History Library Film: 0018097. Retrieved from: Ancestry.com

[3] 1850 US Federal Census, Southern Division, Randolph County, North Carolina; Aaron Hill, head, Dwelling 895, Family 814. NARA Roll: M432-641; Page: 135A; Line 19; Image: 276. Retrieved from: Ancestry.com

[4] 1860 US Federal Census; Western Division, Randolph County, North Carolina; Aaron Hill, head. Dwelling, 1230; Family 1214. NARA Roll: M653-910; Page: 221; Line 11; Image: 446; Family History Library Film: 803910. Retrieved from: Ancestry.com

[5] 1840 US Federal Census, South Division, Randolph County, North Carolina; Aaron Hill, head. NARA Roll: 369; Page: 77; Image: 160; Family History Library Film: 0018097. Retrieved from: Ancestry.com

[6] Williams, M. L. (2016). Descendants of Edward and Priscilla Hill: Generation 1 (pp. 163-172). From Hill Town to Strieby: Education and the American Missionary Association in the Uwharrie “Back Country” of Randolph County, North Carolina (Crofton, KY: Backintyme Publishing Inc.).

[7] Indiana, Death Certificates, 1899-2011 [Database on-line], Aaron Orlando Hill, died: 27 Mar 1926, as cited in Indiana Archives and Records Administration; Indianapolis, IN, USA; Death Certificates; Year: 1926 – 1927; Roll: 05. Retrieved from: Ancestry.com