#52Ancestors – Fresh Start: How DNA rewrote my genealogy

After many years of research on my mother’s family, I had a solidly documented family tree. In fact, I had published a book on that family. Now, the central ancestor of that story, Miles Lassiter, is still firmly in place on my tree. My direct line to him is firmly established. He was my fourth great grandfather, my mother’s, mother’s, mother’s, mother’s, mother’s, father. It’s the spouses that were the problem. I couldn’t see it at first. After all, I had documented everything.

It all started when I became troubled over my efforts to confirm DNA documentation of my third great grandfather, Calvin Dunson, married to Miles Lassiter’s daughter, by his wife, Healy Phillips Lassiter, Nancy Phillips Lassiter. Miles was technically enslaved by the Widow Sarah Lassiter, but Healy, called Healy/Helia/Heley Phillips in most records, was a free woman of color. Thus, all her children with Miles were originally known in public records by the name “Phillips,” rather than Lassiter, since children followed the condition of their mothers, i. e., if enslaved they were enslaved, if free, then the children were free. After Miles was freed from the Widow Lassiter’s estate when purchased by his wife Healy, Nancy and her siblings began to be known by the Lassiter name, though not consistently.[1]

One of the difficulties in determining when Nancy and Calvin married was that no marriage bond has survived. In fact, there may never have been one because they were not a requirement for marriage. On the other hand, I’m not sure why they wouldn’t have sought one since Nancy’s brother, Colier, had one when he married Katherine Polk, though there was none found for the marriage of her other brother, Wiley Lassiter and wife, Elizabeth Ridge. To estimate the date of marriage for Nancy and Calvin, I used the birth date of their oldest daughter, Ellen, my 2nd great grandmother. According to the 1860 census,[2] Ellen was born about 1851; however, her death certificate said 1854. Based on the census, it appeared that Nancy and Calvin had four other children: Rebecca, J. Richard, Martha Ann, and Mary Adelaide. I did find that J. Richard was the child of a possible rape. Nancy sued the perpetrator. I’ve never found any information on the named assailant. Additionally, it appeared that Richard died sometime after 1870. After that, he no longer appeared in the census or other records with the family and he was not named with the other siblings as an heir to the Lassiter estate. So, I determined that Nancy and Calvin married between 1851 and 1854.

Fast forward to my DNA testing.[3] I kept looking for Dunson/Dunston matches. I found one in AncestryDNA. I had hundreds of matches but only one person had a Dunson in her family. Even at that, it appeared that it was one of her other lines that was my connection to her. So, she probably wasn’t a Dunson match.

While at a genealogy conference, I mentioned my puzzlement to some of my genie friends and colleagues. One mentioned that she was a Dunson descendant. With that we began searching to see if we were a match or if I matched any of her other known Dunson cousins who had DNA tested. She checked especially on GEDmatch, a third-party site when individuals having tested their DNA on various sites can upload their results, thus expanding their chances of learning about more family members. We did not find a single match. Not one. I figured that my branch did not have descendants who had tested yet or uploaded to GEDmatch. This was several years ago when the databases did not have the numbers of individuals who have tested that they have today. Still, it bothered me. I had it documented in multiple places, Calvin Dunson was the spouse of Nancy Lassiter and the father of Ellen. I couldn’t explain the DNA; it was a conundrum.

One day I was talking to someone, G. C., who was commenting on the connections between his Cranford ancestors, especially Samuel “Sawney” Cranford, and Miles Lassiter. He noted that they were both Quakers, members of the same Meeting. I commented that, apparently, we didn’t just have business and social dealings, but we were somehow related. I told him I had several Cranford DNA matches. I speculated that if he tested, we might be a DNA match as well. After we got off the phone, I was reflecting on our conversation, when I suddenly had a revelation. I realized that I needed to follow the DNA to find the answers. I needed to let the DNA tell me what the genealogy was, not just the paper trail.

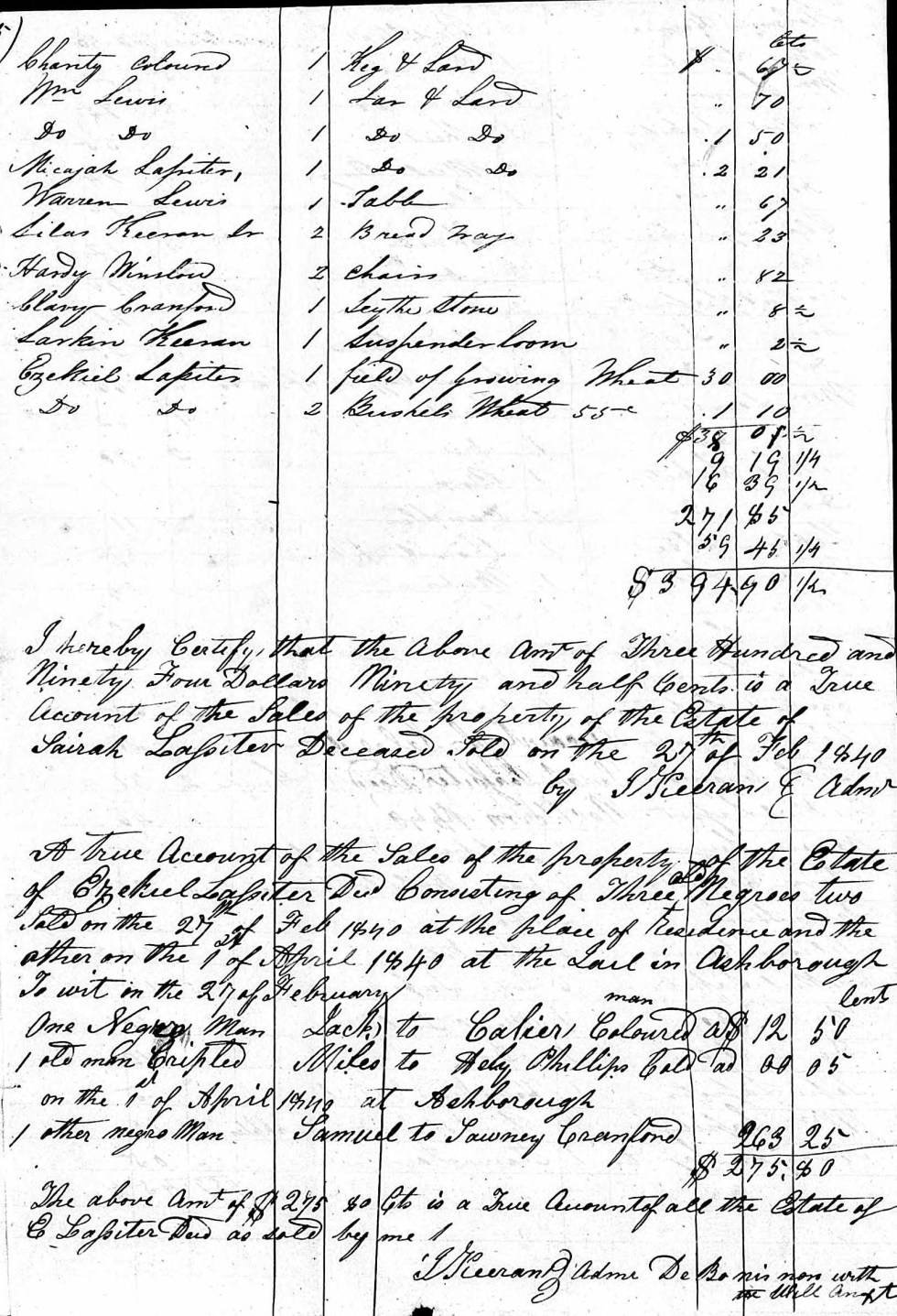

It occurred to me that Sawney Cranford had played an important role in the lives of Miles and his brothers, Jack and Samuel, especially Samuel. When the Widow Lassiter died, a final stipulation of her husband Ezekiel’s will was enforced. According to the will, Miles, Samuel, and Jack were to be under the control of Ezekiel’s widow until she died. She died in 1840, at which time both estates reached final settlements.[4] As part of Ezekiel’s final accounting, the only property mentioned were the three men, old men at this point. They were offered for sale. Miles’ wife, Healy, purchased him from the estate. Miles’ son, Colier, purchased Jack. Both men were purchased for nominal amounts of money. However, according to the estate information, Samuel had been a runaway, apprehended in Raleigh. There were associated expenses with his capture: newspaper ads, jail time, transport back to Randolph County. The fees, $262 worth, were paid by Sawney Cranford, thus purchasing Samuel. That’s the same Sawney Cranford who was G. C.’s ancestor. I realized that my DNA matches were also descendants of Sawney Cranford. A light bulb went off. I was descended from Sawney Cranford! If that was true, where was the connection? Sawney was a contemporary of Miles and Healy. So, his children were contemporaries of Miles’ children, well some of his children anyway. Sawney had children that spread over a wide time period. Based on the centimorgans (cMs), I shared a third great grandparent. Well, it wasn’t Nancy or Calvin was my first thought. That doesn’t make sense. I had the documentation, but the DNA seemed to be saying otherwise. Then I began to think back to some other documents I had.

After Miles died, it appears that there was a need to raise funds. Miles’ son, Colier, began purchasing interests in the family land from his siblings and then taking out a Deed of trust. As part of that process there seemed to be a hastily filed intestate probate for Miles’ wife, Healy, called “Healy Phillips or Lassiter.” Oddly the document had no date on them. However, they were filed in Will Book 10, which covered the years 1853-1856 with Healy’s papers mixed in with others from 1854 and 1855.[5] In them, all the children, heirs, were named, including Nancy. She, like her siblings, was called “Phillips or Lassiter.” There was no mention of her being married in any of the above-named documents.

One clue to these legal actions seemed to be found in a letter written in 1851, on behalf of Colier, by Jonathan Worth, a local attorney who later became governor of North Carolina. In the letter, Worth stated that Healy had four children from a previous marriage, with whom it would be necessary to share her estate along with the seven children with Miles. The other alternative was to buy out the four other children. I’m speculating that the other documents pointed to efforts to raise the monies to buy out the four half siblings. What I realized also was that not one of these documents referred to my 3rd great grandmother, Nancy, as Nancy Dunson, wife of Calvin Dunson. Not one.

The first time Nancy is referenced as married in any public document located so far by me was in the lawsuit for the assault and subsequent bastardy bond in 1858.[6] By that time, not only was there the son, J. Richard, subject of the lawsuit, but another sister, Sarah Rebecca, born about 1857. Therefore, there is reasonably solid information that Ellen was born between 1851-1854. There was one more piece of information that helped determine her age, her marriage certificate. The record I had seen does not mention her age. That’s okay, because using her date of marriage was sufficient.[7]

Ellen Dunson married Anderson Smitherman on 23 Sep 1865, in Randolph County. I repeat, 1865. If Ellen was born as late as 1854, she would only have been 11 years old. I know that there were no regulations for minimum age in those days, but eleven is extremely young. I really can’t say that I can find another incidence of an eleven-year old marrying in my family. There may be some in other families, but not in mine. It is far more likely that Ellen was born in 1851 or 52. That would make her thirteen or fourteen when she married, still very young, but not unprecedented. With that reality, it was most likely that Ellen was not the biological child of Calvin Dunson, even though she carried the Dunson name, was named as one of his heirs,[8] and his name was listed as her father on her death certificate.[9] I realized Ellen was born five years before her next closest sibling, Sarah Rebecca, was born, or before any legal documents referred to Nancy as Nancy Dunson, wife of Calvin Dunson.[10] Putting it all together, it appeared that my 2nd great grandmother Ellen was most likely the Cranford descendant.

Based on my DNA matches, it appeared that the most likely candidate was a son, Henry. My closest matches are with his direct descendants. Altogether I have identified 32 of my matches as Cranford descendants. At this time, I have no information that sheds any light on what led to Nancy having a child with Henry. They were not cited in the Bastardy Bonds of the time. I can’t really say I’m very concerned with that. What I do know is that I have since developed a very good relationship and communication with G. C. and other Cranford relatives. I also still have an interest in the Dunsons because Calvin and Nancy’s descendants are still my cousins. They do have a Dunson legacy.

DNA has expanded, broadened, my family connections and given me new perspectives on my relationship to my community, Randolph County. DNA has helped me break down brick walls and confirmed oral tradition and given me the surprise of rewriting my family story. Did I say “surprise,” singular? My mistake. Yup, I realized I had another ancestor who was well documented, but whom DNA said was not my ancestor, in the same family line! This time, it was my great grandfather, … but that’s a story for another day.

References

[1] Williams, M. L., (2011). Miles Lassiter (Circa 1777-1850) An Early African American Quaker from Lassiter Mill, Randolph County, North Carolina: My Research Journey to Home. Palm Coast, FL (Crofton, KY): Backintyme Publishing, Inc. All the information for this essay on Nancy and the family is based on documentation provided in Miles Lassiter.

[2] 1860 US Federal Census, Western Division, Randolph, North Carolina; Calvin Dunson, head; Nancy Dunson, & Eallen [sic] Dunson, age 9; Sarah, age 3; Richard, age 1. NARA Roll: M653-910; Page: 212; Image: 429; Family History Library Film: 803910. Retrieved from: Ancestry.com

[3] My DNA testing referenced in this article is specific to my matches at AncestryDNA.

[4] Obituary of Miles Lassiter. (1850, June 22). Friends Review iii,700.

[5] Estate of Healy Phillips or Lassiter. (1854-1855). Randolph County, Randolph County, North Carolina Will Book 10:190-192. FHLM #0019645. See also North Carolina, Wills and Probate Records, 1665-1998. [Database and Images on-line] Henly Phillips. Digital Images: 1225-1229. Retrieved from: Ancestry.com

[6] Nancy Dunson v. John Hinshaw, 2 November 1858, Minutes of the Court of Common Pleas and Quarter Sessions, FHLM #0470212 or #0019653.

[7] North Carolina, Marriage Records, 1741-2011 [Database and Images on-line]. Anderson Smitherman and Ellen Dunson, 23 Sep 1865. Retrieved from: Ancestry.com

[8] North Carolina, Wills and Probate Records, 1665-1998 [Database and Images on-line]. William Dunston, 1892. Digital Images 1393-1398. Retrieved from: Ancestry.com

[9] North Carolina, Death Certificates, 1909-1975 [Database and Images online]. Ellen Mayo, died: 12 Jun 1920. Retrieved from: Ancestry.com

[10] 1870 US Federal Census: New Hope, Randolph, North Carolina; Calvin Dunson, head; Nancy Dunson; S. A. R. (Sarah Rebecca); J. A. [sic] (J. Richard); M. A. (Mary Adelaide); and M. Ann (Martha Ann). NARA Roll: M593-1156; Page: 400B; Image: 250; Family History Library Film: 552655. Retrieved from: Ancestry.com